Highlights

Gunpowder Flasks and Cans

Gunpowder flasks also known as powder flasks were used by hunters and soldiers to carry their supplies of gunpowder in the 1800s and were found in a high percentage of American households. Most flasks were made of copper and were essentially metal upgrades from the powder horns of the eighteenth century. Hagley has a collection of 400 flasks.

In addition to flasks, Hagley also has a large collection of over 700 gunpowder cans covering a variety of manufacturers and designs, including DuPont, Laflin & Rand, The Hazard Powder Company and lesser-known companies such as the Eureka Powder Works and the King Powder Company. Traditional imagery on gunpower can labels would feature dogs, game animals, guns, and horns.

DuPont Advertising Art

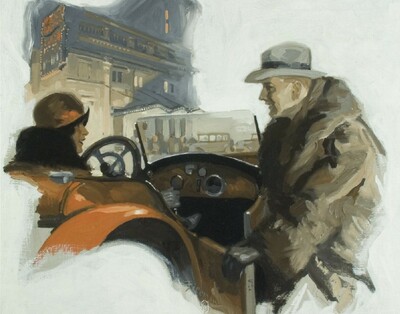

Beginning in the late 1890s, DuPont began commissioning artists to create paintings on specified subjects which represented their products. The earliest and largest group were used to promote purchasing smokeless gunpowder for hunting. Topics focused on hunting and trapshooting. Most included sporting dogs – mainly setters. They were used in a variety of ways such as being reproduced on calendars, trap hangers to hang in trapshooting clubhouses, envelope covers, postcards and prints.

Paintings were commissioned for DuPont Magazine covers from 1918 to 1928 with most of them from 1919. Artists included Herbert Stitt, Charles MacLellan, George Pierce, Harvey Dunn and more. Topics included hunting and trapshooting; dynamite and blasting for coal mines and agricultural uses; Fabrikoid (DuPont’s artificial leather); World War I; paints; and even Scrooge for a 1926 December issue.

During the 1920s, paintings were commissioned for print advertising in magazines such as Good Housekeeping for advertisements on DuPont paint. Most of these feature DuCo car paint but there are also paintings made to promote DuPont furniture and house paint. Many of these images include or feature women because women were becoming a strong influence on the market and discovering their purchasing power.

Fred M.B. Amram & Sandra A. Brick Woman Inventor Collection

Throughout American history, women inventors, entrepreneurs, managers, and workers in many fields have made profound impacts on the growth of our nation’s enterprises and on our economic vitality. The history of American enterprise would not be complete without compelling stories of women creating new products, starting new companies, leading organizations, and advocating for workplace equality. Not only have women made landmark contributions to American commerce and innovation, but they have done so while overcoming socially determined gender roles. Over time, however, these contributions have not been fully recognized, appreciated, or integrated into the stories we tell about America’s enterprise history.

The Amram/Brick Women Inventors Collection was created to celebrate woman’s ingenuity and encourage the slowly growing proportion of patents issued to women. In the 19th century about one-half of one percent of patents included the name of a woman. During 1957 that number was only one and one-half percent and by the beginning of the twenty-first century roughly twelve percent of patents were received by women. Fred Amram and Sandra Brick intend this collection, and education programs based on it, to stimulate more people to realize women’s creative potential to the point that half of all U. S. patents are issued to women inventors.

Portraits by Rembrandt Peale

Rembrandt Peale’s work is represented in Hagley’s collection through six portrait paintings (Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours, Margaretta Lammot du Pont, Sophie du Pont, Evelina du Pont, George Washington, and Martha Washington) and two attributed sketches (E. I. du Pont and Victor Marie du Pont).

Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860) was an American portrait painter most well-known for his portraits of George Washington. He was born on February 22, 1778, in Bucks County, Pennsylvania to his mother, Rachel Brewer, and his father, Charles Willson Peale. Charles was a noted artist, and he taught his children to paint scenery and portraiture from a very early age. Rembrandt’s siblings were also named after revered artists of the past: Rubens, Titian, Ramsay, Raphaelle, Sophonisba, Angusciola, and Angelica Kauffman.

Rembrandt was thirteen years old when he completed his first work, a self-portrait. He would go on to produce more than one thousand works in his lifetime. Philadelphia was Rembrandt’s hometown, but he traveled up and down the east coast from Boston to Charleston. Rembrandt also spent extended periods abroad.

His father’s artistic renown made it possible for Rembrandt to paint the portraits of many important figures. In 1795, George Washington agreed to three sittings over three days for Rembrandt to paint his portrait. Rembrandt, at only seventeen years of age, painted a wonderfully accurate depiction of the then sixty-three-year-old George Washington.

In the following years, Rembrandt was determined to produce a more idealized portrait of the President; one that captured the heroic and confident qualities held in the minds of many Americans. In 1823, Rembrandt succeeded in his goal with a portrait of George Washington entitled Patriae Pater. He would eventually create close to eighty copies of that work.

Patent Models by Women Inventors

During the nineteenth century, women received less than 1% of all United States patents. Out of Hagley’s large patent model collection of about 5,000 models, there are currently 68 invented by women which supports this statistic.

Of these patent models laundry-related patents are the largest category. Other are related to food, furniture, shoes, textile-related including sewing machines, medical, stoves, marine and horse-related items such as a stirrup.

Crowninshield Garden

The Crowninshield Garden is a ca. 1920s neoclassical garden designed by Louise du Pont Crowninshield and her husband Frank Crowninshield and built on the terraced ruins of Eleutherian Mills––the first DuPont Company industrial site in the United States. Operating from 1803-1921, Eleutherian Mills was the foremost gunpowder production manufactory in America. The site was the foundation of a sprawling global chemical and business empire tied to the du Ponts, who rose to become one of the wealthiest families in the world by World War I. The garden constructed on top of the ruins of this historic industrial complex during the 1920s appears to have been constructed slowly over the course of a decade by local craftsmen and by the Crowninshields themselves, who attempted to create exact scale replicas of architectural features they had observed on their travels in Italy. It is a provocative combination of classical ruins, industrial ruins, and the ruins of time.

The garden was an inspiration to professional and amateur artists. Hagley’s collection contains some of these artistic works.

Many of the architectural features that the Crowninshields placed in their garden have been added to the collection as well.

Crafted for the Hearth: Nineteenth-Century Hooked Rugs

Originally made to be placed on the hearth to catch sparks from the fire, hooked rugs quickly became useful in other areas of the house. The earliest floral rugs were made with free hand designs. By the 1840s, hooking rugs was widespread throughout the New England states. Burlap's availability for the backing following the Civil War made hooked rugs much easier to make and extremely popular.

Printed rug patterns were available by the 1850s, but it was Edward Sands Frost (1843-1894), an enterprising tin peddler from Biddeford, Maine who recognized the growing popularity as well as commercial potential of handmade rugs. He was the first to create successful commercial hooked rug designs by making metal stencils and selling printed patterns on burlap in the 1870s.

Rug hooking declined during the late 1800s with the development of industrially manufactured carpets but has never entirely gone away due to several revival periods.